Wouter F.M. Henkelman (EPHE IVe/PSL, Paris)

In his inauguration speech of March 4th, 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt famously declared “The only thing we have to fear, is fear itself.” The statement referred to the Great Depression, which was then reaching its zenith, but often has been taken as a reflection on – and an answer to – the darkening political skies of the 1930s. In Germany, the Nazi party came to power on the next day, March 5th, inaugurating twelve years of world-wide suffering on an unprecedented scale.

As Matthew Stolper has recently described, the discovery of the Persepolis Fortification archive took place in the middle of global turmoil, on that very same day, March 4th 1933. Ernst Emil Herzfeld, then the excavator of Persepolis, sent a telegram to James Henry Breasted, director of the Oriental Institute in Chicago, to announce the discovery of “Hundreds probably thousands business tablets” on the Persepolis terrace. Their excavation would keep his team busy for many months to come. Thus, on June 17th, 1933, Herzfeld’s deputy Friedrich Krefter noted in his diary “(I) excavated tablets with Suleiman the entire morning. Most are so soft that they break. Many interesting seals. Two tablets with Aramaic in ink, one incised with Aramaic. In the afternoon correspondence and tennis.”

The many thousands of Elamite, Aramaic and uninscribed tablets excavated in Persepolis form what is now known as the Persepolis Fortification Archive. Upon a signed loan agreement between Iran and the United States, they were carefully packed and shipped to the University of Chicago for study and publication. Another, smaller, archive, from the Persepolis Treasury was divided between Iran and Chicago.

Among the pioneers to study the challenging Elamite tablets were George Glenn Cameron (1905-1979) and Richard Treadwell Hallock (1906-1980), both of whom devoted a major part of their scholarly life to this work. Their publications, Cameron’s Persepolis Treasury Tablets (1948) and Hallock’s Persepolis Fortification Tablets (1969) still stand today as the towering basis upon which all later scholarship on Achaemenid administration is grounded. Pride was not at all the feeling of the first students of the Elamite archives, however. Cameron privately expressed his insecurity and desperate need to consult with senior colleague. In fact, he had been on his way to Leipzig to meet the Franz Heinrich Weißbach on the day that Germany invaded Poland (September 1st, 1939). Cameron would never meet Weißbach: the visionary scholar of the Achaemenid royal inscriptions died in the basement of his home in Markleeberg during an allied bombardment in 1944. Four years later, in the preface of his edition of the Treasury tablets, Cameron would wryly describe his work on the texts as “a lonely one.”

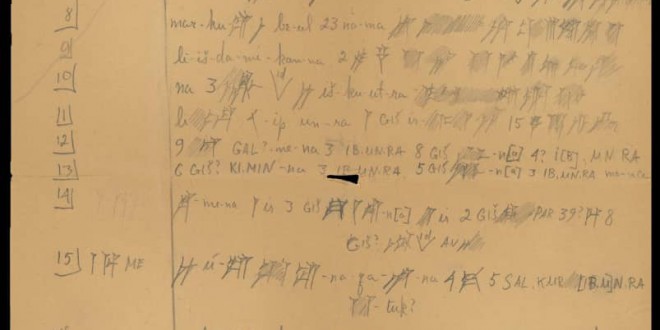

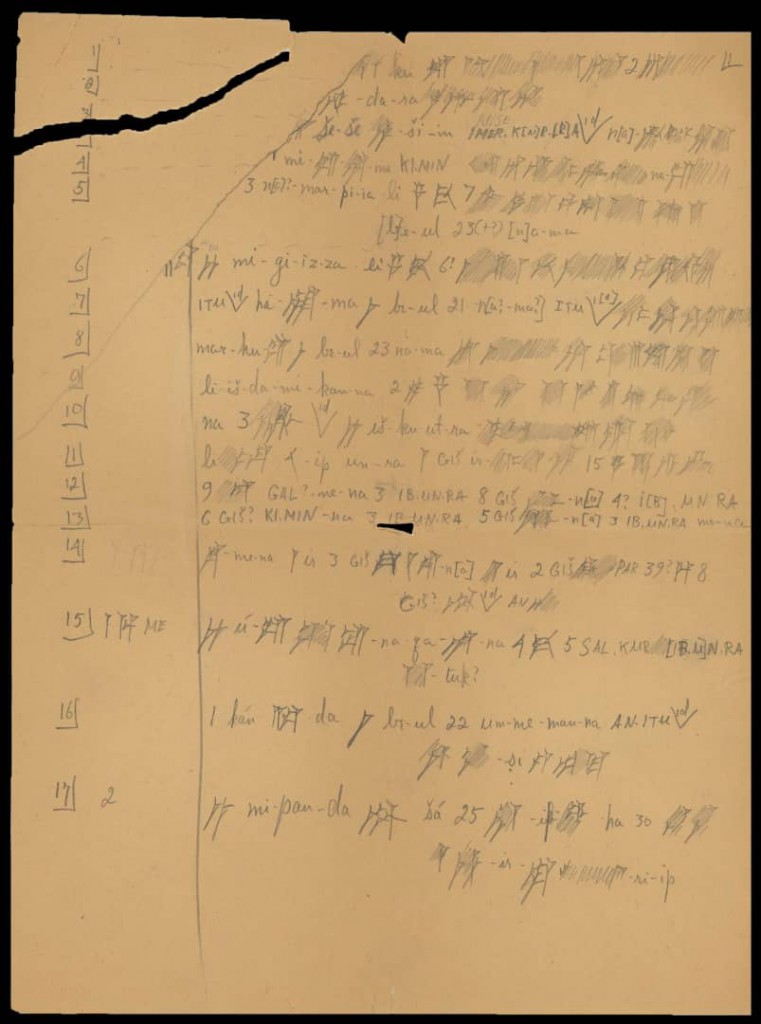

As I write these lines in commemoration of the find of the Persepolis tablets, a few faded and crumbling of Depression-age paper lie in front of me on my desk in the Oriental Institute, Chicago. They contain a first edition, by Cameron, of a Persepolis Fortification tablet now known as “NN 2655” and appear to be written in the late 1930s or early 1940s. Nothing could reflect more the immense progress that has been made in the last 86 years than these notes that are a mix between a hand copy and very tentative transliteration. Cameron, then already an experienced cuneiformist, had trouble recognizing or interpreting individual signs, even including number signs. He was in no position to imagine the Fortification archive or its setting in the Achaemenid world in the way we do today and yet his work and that of Hallock made all our current views possible.

NN 2655 was provisionally edited by Charles Jones, who continued the work of his teacher, Hallock, after the latter’s death in 1980. His edition has never been published, just as many of Hallock’s own editions. The Oriental Institute authorized me in 2006 to (re-)publish all texts available in manuscript, a number of entirely new texts first edited by Matthew Stolper, as well as texts previously published by Hallock. In my work, I profit greatly from close collaboration with Matthew Stolper and with Mark Garrison, the master of Achaemenid seal studies. The publication, part of the output of the Persepolis Fortification Archive Project directed by Matthew Stolper, will contain some 5500 discrete texts and will present the Elamite part of the Fortification Archive in a novel way based on discoveries I made in the National Museum of Iran, where Dr. Jebrael Nokandeh generously granted me access to tablets already in Tehran (most of which have recently been published by Abdolmajid Arfaee). The discoveries entail, briefly, the ancient way of organizing the archive and they allow me to reconstruct original ‘files.’ This, and the great advances in our understanding of the Elamite language, are reasons to (re-)publish the 5500 in a single volume with updated transliterations, translations, and commentaries.

As I hold tablet NN 2655 in my hands and read the lines written in year 21 of king Darius I (501/500 BCE), I recognize names and phrases familiar to me from 25 years of engagement with the archive. The tablet is a so-called journal (register), with multiple entries on individual transactions. The first involves a makuš who receives barley for a series of sacrifices, including one for Išpandaramattiš, a name that my Iranian colleague Shahrokh Razmjou splendidly recognized as that of the goddess Spenta Ārmaiti. Other entries include one mentioning a horse with personal name (the first time such a name is attested); one dealing with a mixed group of Skudrians (from northwestern Anatolia or beyond) directed by a female leader; and several citing officials with the designation karamaraš (*kāra-(h)māra-), “people counter” or “registrar.” This last category is particularly interesting, as such registrars are now known to have played a crucial role in drafting workers and soldiers, in monitoring irrigation networks, and in assessing taxes. They certainly were pivotal in organization and management of the Achaemenid world. Finally, at the end of text NN 2655 (lines 35-36) an amount of grain is mentioned that apparently had not been used correctly: anše.kur.ra ber zikkakana napanna ha huttukka mil haba, “(it) was to be deposited for ber horses, (but instead) it was used for the gods. Open an enquiry!” For the modern editor, the directness of such a remark is electrifying, as it seems to afford an almost face-to-face contact with scribes and administrators working two and half millennia ago.

As has often been remarked, certainly in recent years, the Persepolis Fortification archive provides an unparalleled window to the heartland of the Achaemenid empire during the crucial middle years of the reign of Darius I. It provides unique and often quantifiable evidence on such subjects as animal husbandry, royal roads, taxation, landed estates of noble Persians, and agricultural production. The area under purview of the Persepolis administrators was large, stretching from the Rām Hormoz or Behbahān area all the way to Nīrīz (ancient Narezzaš), where, according to the tablets, the funerary monuments of Cambyses and his queen Upandush were situated. In all the lush valleys and well-watered plains monitored by the archive, an ‘institutional landscape’ had emerged: the amalgam of human and material elements assigned and built by the institutional economy. Apart from an intricate hierarchy of district suppliers, labour-logistics officials, way-station managers, inspectors, registrars, etc. this system had a tangible presence in roads, bridges, sluices, irrigation canals, reservoirs, granaries, fruit plantations, garrison sites, way stations, cultic installations, centres of craft production, and villages of dependent labourers brought from other parts of the empire.

The type or model of administration introduced by the Achaemenid kings in the heartland of their empire also emerged, as recent finds show, in more distant satrapies such as Arachosia and Bactria. It is safe to say that it fundamentally and enduringly impacted the human experience in those lands. This is also the essential importance of the study of the Persepolis Fortification Archive: its potential to enrich, transform and invigorate Achaemenid studies. As Pierre Briant, eminent historian of the Achaemenid world, has repeatedly stressed the future of research on ancient Iran lies in these unassuming little tablets; whichever country holds the Persepolis Fortification Archive will by definition be the centre of Achaemenid studies for many generations to come.

Today, as 86 years ago, clouds are again gathering in the skies and people all over the world are once more facing a period of increased uncertainty and heightened tensions. It is in – and despite – this darkening atmosphere that the return of the Persepolis tablets from Chicago to Iran will soon commence. The event will mark much more than the repatriation of precious objects that rightfully belong to Iran since the tablets contain not only an undreamt amount of new data, but also convey a new idea about one of the most formative periods in Iranian history. As they will be studied more and more by Iranian scholars, they will undoubtedly continue to inform the study of ancient Iran and transform that discipline as such. It fills me with pride that these same scholars will continue in the footsteps of Cameron and Hallock, will profit from the treasures uncovered by the Persepolis Fortification Project, and, most importantly, will fulfil the august promise that Herzfeld recognized when he saw the tablets emerge from the dust of centuries.

Scholars may not have the same impact as presidents, but they do share with them the moral obligation to fight fear and ignorance. The immanent return of the tablets will be a small but meaningful shimmer of hope. It offers a chance to broaden the horizons of the Iranian past, to explore new pathways in the study of the human experience and, most and for all, to do so in the spirit of true cooperation and in thankfulness to those who preceded us.

Select references

Arfaee, A. 2008, Persepolis Fortification tablets: Fort. and Teh. texts (Ancient Iranian Studies 5), Tehran.

Briant, P. 2017, De Samarkand à Sardes via Persépolis dans les traces des Grands Rois et d’Alexandre, in: Jacobs, Henkelman & Stolper (eds.): 825-52.

Cameron, G.G. 1948, Persepolis Treasury Tablets (Oriental Institute Publications 65), Chicago.

Fisher, M.T. & Stolper, M.W. 2005, Achaemenid Elamite administrative tablets, 3: Fragments from Old Kandahar, Afghanistan, arta 2015.001.

Garrison, M.B. 2017, The Ritual Landscape at Persepolis. Glyptic Imagery from the Persepolis Fortification and Treasury Archives (Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 72), Chicago.

Garrison, M.B. & Root, M.C. 2001, Seals on the Persepolis Fortification tablets, vol. 1: Images of heroic encounter (Oriental Institute Publications 117), Chicago.

Hallock, R.T. 1969, Persepolis Fortification Tablets (Oriental Institute Publications 92), Chicago.

Henkelman, W.F.M. 2003, An Elamite Memorial: the šumar of Cambyses and Hystaspes, in: W. Henkelman & A. Kuhrt (eds.), A Persian Perspective: Essays in Memory of Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg (Achaemenid History 13), Leiden: 101-172.

–––– ۲۰۱۷a, Humban and Auramazdā: Royal gods in a Persian landscape, in: W.F.M. Henkelman & C. Redard, Persian religion in the Achaemenid Period / La religion perse à l’époque achéménide (Classica et Orientalia 16), Wiesbaden: 273-346

–––– ۲۰۱۷b, Imperial signature and imperial paradigm: Achaemenid administrative structures across and beyond the Iranian plateau, in: Jacobs, Henkelman & Stolper (eds.): 45-256.

Jacobs, B., Henkelman, W.F.M. & Stolper, M.W. (eds.) 2017, Die Verwaltung im Achämenidenreich – Imperiale Muster und Strukturen / Administration in the Achaemenid Empire – Tracing the Imperial Signature (Classica et Orientalia 17), Wiesbaden.

Jones, C.E. & Stolper, M.W. 2003, s.v. Hallock, Richard Treadwell, in: Encyclopaedia Iranica 11: 592-4.

Razmjou, S. 2001, Des traces de la déesse Spenta Ārmaiti à Persépolis et proposition pour une nouvelle lecture d’un logogramme élamite, Studia Iranica 30: 7-15.

Stolper, M.W. 1977, Three Iranian loanwords in Late Babylonian texts, in: L.D. Levine & T.C. Young (eds.), Mountains and Lowlands: essays in the archaeology of Greater Mesopotamia (Bibliotheca Mesopotamica 7), Malibu: 251-66.

–––– ۱۹۸۰, George G. Cameron 1905-1979, Biblical Archaeologist 43: 183-89.

–––– ۲۰۱۷, The Oriental Institute and the Persepolis Fortification Archive, in: Jacobs, Henkelman & Stolper (eds.): xxxvii-lix.

Weißbach, F.H. 1890, Die Achämenideninschriften zweiter Art (Assyriologische Bibliothek 9), Leipzig.

–––– ۱۹۱۱, Die Keilinschriften der Achämeniden, Leipzig.

Websites

https://oi.uchicago.edu/research/projects/persepolis-fortification-archive

http://www.achemenet.com/en/tree/?/textual-sources/texts-by-regions/fars/the-persepolis-fortification-archive/persepolis-fortifications-tablets#set

انجمن علمی باستانشناسی ایران پورتال رسمی انجمن علمی باستانشناسی ایران

انجمن علمی باستانشناسی ایران پورتال رسمی انجمن علمی باستانشناسی ایران